Shenandoah is sometimes humorously referred to as the Switzerland of America, not so much probably for its beauty which, until man came to mar it with strip mining, was great, but because the town itself is situated in a basin whose periphery is surrounded by mountains. The distinguishing feature of the town, however, is the fact that it is only one square mile large; yet, in this small area, in 1915, there were 27,500 souls living closely knit together1, and of this number about 25 percent were Poles. Today the ratio is over 40 per cent of the total population of 19,600.2

When did the Poles come to Shenandoah? How did they get there? What hardships did they endure in the process of establishing themselves as respectable citizens in an environment hostile to them? Their story is an epic of Polish immigration to the coal fields of Northeastern Pennsylvania.

According to reliable sources, the first Poles in Shenandoah were three young men - Michael Radziewicz, Alexander Babin, and Joseph Lizewski who came to America about 1862, probably to better their economic status. With all the optimism of youth, they did not care what work they would be asked to do as long as the remuneration was adequate, or where they would stop to make their homes, for it appears they had no relatives in this country. Destiny, in the guise of an agent who purchased tickets for them to a tiny settlement called Park Place, helped these adventurous Poles select the anthracite region. The reason why Park Place became the terminal of their trip was a very practical one-all the money they possessed covered the fare only to this point. Here, however, there was no work for them. With empty pockets and heavy valises but light steps they trudged eight miles on foot to Shenandoah to which they were directed by a fellow Slav, a railroad worker, who told them that there coal mining offered better opportunities.

The town had been surveyed and plotted in the spring of the same year by the Philadelphia Land Company, which anticipated the tapping of a rich vein of coal.3 Shenandoah, at that time, boasted of one frame building, a hostelry, about a dozen shacks, and the newly constructed Shenandoah City Colliery.4 The population approximated less than one hundred inhabitants and a few Indian stragglers living on Indian Ridge. The new arrivals found a job in the mine operated by Miller, Rhoades, and Company. Shenandoah, incorporated as a borough January 16, 1866, became the greatest center of anthracite production in the southern coal fields located in Schuylkill County. It drew many Polish immigrants who usually came to join their relatives or friends living in Shenandoah who helped them get jobs.

During the seventies there were about five hundred Poles living in Shenandoah and the neighboring places. These years were turbulent ones. Acute troubles between capital and labor agitated the country, especially the mining regions and particularly Schuylkill County. Although several labor unions were organized in the county from 1868 to 1887,5 the Poles were not active participants in the labor movement, because they were not sufficiently orientated in the socio-economic problems of the day. In 1897 the United Mine Workers of America, under the leadership of John Mitchell, succeeded in making many converts among the Polish miners.6

Whether the Shenandoah Pole was a union member or a non-union man, he suffered with the rest of the strikers during a walk-out. Often arbitration ended in a deadlock between the union men and the operators, bringing on a prolonged strike. Then strikers, living in company houses, were evicted; their credit at the company store was foreclosed; and the union treasury, drained of its resources, could not aid them. Many times the workers were starved into submission, losing more than they gained. A few dates, chosen at random, show how prevalent were the strikes: in 1870, four months; in 1871, four months; in 1875, six months; in 1902, almost six months; in 1925, six months.

Another source of annoyance were the Molly Maguires, an organization composed of miners who struck chiefly against the intolerable conditions in the mines.7 Some authors hail the Mollies as martyrs of labor, others classify them as criminals. It is not the writer's intention to discuss the origin of the Molly Maguires and their deeds, but to give a background for an understanding of the Mollies' operation in the anthracite field and the subsequent effects upon the Polish immigrants in Schuylkill County where the Mollies were very strong. The following quotation is taken from The Molly Maguires by F.P. Dewees:8

The magnitude and lengths of the "strikes" in the coal regions combined with the influence of those "strikes" have drawn special attention to the "Laborers' and Miners' Union," and an impression has to some extent obtained that the "Labor Union," if not identical, is at least in earnest sympathy with the "Molly Maguires." The only color for such a charge exists in the fact that the great majority of the "Mollies" belong to the "Union," and that the counsels of such members were naturally for violent rather than peaceable redress, and, further, that most of the notorious outrages committed by "Mollies" were against capital as represented in property or in the persons of superintendents and bosses.

"Fears of the dreaded `Molly,' during the strike of 1875, prevented open revolt on the part of those willing to go to work." 9 The Polish laborer did not perpetrate any destruction of company property, neither did he indulge in the outrages committed against the mine personnel; in fact, he was willing to break the strike by working, since his meager earnings meant so much to his family. The Polish worker was often intimidated by threats or a beating to join the strike.

There were times when the Poles ignored the warning and went to work. They were called "scabs" and chased by the Mollies, sometimes barely escaping severe punishment. Old timers recall how they shouted as they rushed into their homes pursued by the Mollies: "Mother, hurry up and lock the doors and windows because the Molly Maguires are after me." Many a worker did not dare show himself at the shaft, after he had received the following quaint note graphically illustrated with a crude coffin or skull and cross bones or some other gruesome drawing:

Any blackleg that takes a Union Mans' job while He is standing for His Rights will have a hard Road to travel and if He dont he will have to suffer the consequences.10

By 1880, the Mollies' power was broken through court reprisals; nevertheless, the Poles were harassed by another type of tormentors. Polish families usually raised vegetables and kept chickens, ducks, pigs, and a cow or two. During strikes, roving bands of unemployed and lawless men stole the "Polander's" fowls or pigs or cow. The Poles resisted such thefts sometimes at the point of a gun.

To eke out a living, Polish workers were often constrained to send their young sons to work on the breaker or underground. Breaker boys, whose ages ranged from ten to fourteen, sat astride long chutes and picked out the rock and slate from the screened coal traveling downward to the empty freight cars beneath the chutes. Sixteen year old boys either drove mules hitched to empty cars, which they delivered to the miners and brought back to the surface filled with coal, or opened and closed doors at the bottom of the shaft. Old Polish miners recall seeing Polish women picking slate. Modern screening machinery, public opinion, and state legislation ended the exploitation of child labor.

Gloom and sorrow settled over Shenandoah one fatal day, November 12, 1883. A serious fire broke out in the United States Hotel and reduced half of the town to ashes.11 Many Polish families lost all their possessions in the consuming flames. But the courage that brought them to the shores of America served them again in weathering the destructive effects of the catastrophe. With faith in themselves, they set out to build new homes on the grey cold ashes that represented a lifetime of diligent saving.

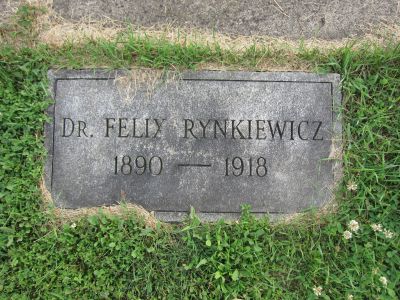

Slowly the Poles acquired business acumen. Joseph Rynkiewicz, who joined his brother Felix in 1872, became one of the early well known businessmen. At first he worked in the mine where he was injured by a fall of rock and coal in 1882. Recovering a year later, he engaged in the general grocery and provision business, adding thereto a steamship agency and private banking. Others followed his example. They bought and developed, or they set up, business enterprises, such as taverns, stores, bottling works, etc.

By World War I, the Poles were becoming more and more prominent in municipal government. One of the best beloved figures was the late chief burgess Charles Magelango, who served several terms and died in office. The present incumbent is of Polish extraction.

St. Casimir's parish was organized in 1872. Rev. Andrew Strupinski assumed the pastorate over 300 Poles scattered throughout Shenandoah and the vicinity. At first, services were held in the German-Catholic Church until the Poles built a wooden chapel on North Jardin Street. The wooden structure was replaced by a brick building, and in 1915 a new edifice was erected. St. Casimir's Church, considered the largest and most beautiful in that area, is the oldest Polish Church in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.12

The second pastor was Rev. Joseph Lenarkiewicz (1877-1904). This zealous priest transformed the wooden chapel into a large brick church; he built a rectory, convent, and school and entrusted the parish school to the Bernardine Sisters in 1899.13

Another Polish parish, St. Stanislaus, was organized in 1898. A church was erected on the corner of Cherry and West Streets. Three years later, a parochial school was established and staffed by the Bernardine Sisters.14

A word must be said about Polish organizations, often called the ramparts of the Polish cause. St. Casimir's Benevolent Association was organized February 14, 1875, with twenty-four members. Sylvester Brocius was elected president and Felix Murawski, secretary. The National Guards of Warsaw were organized June 1876, with fifteen members. The first president was Joseph Janicki, while Joseph Konopnicki was the first secretary.15

The Poles' love of pageantry manifested itself in thirty-five different organizations, several of which had uniforms. Patriotic rallies were colorful affairs, and all of Shenandoah turned out to see the "Polanders." The non-Polish residents may have not understood what was said, but they certainly feasted their eyes on the motley of colors arrayed before them. Even today the older generation sighs and repeats that those were the days. Large Polish fraternal organizations have absorbed most of the local societies.

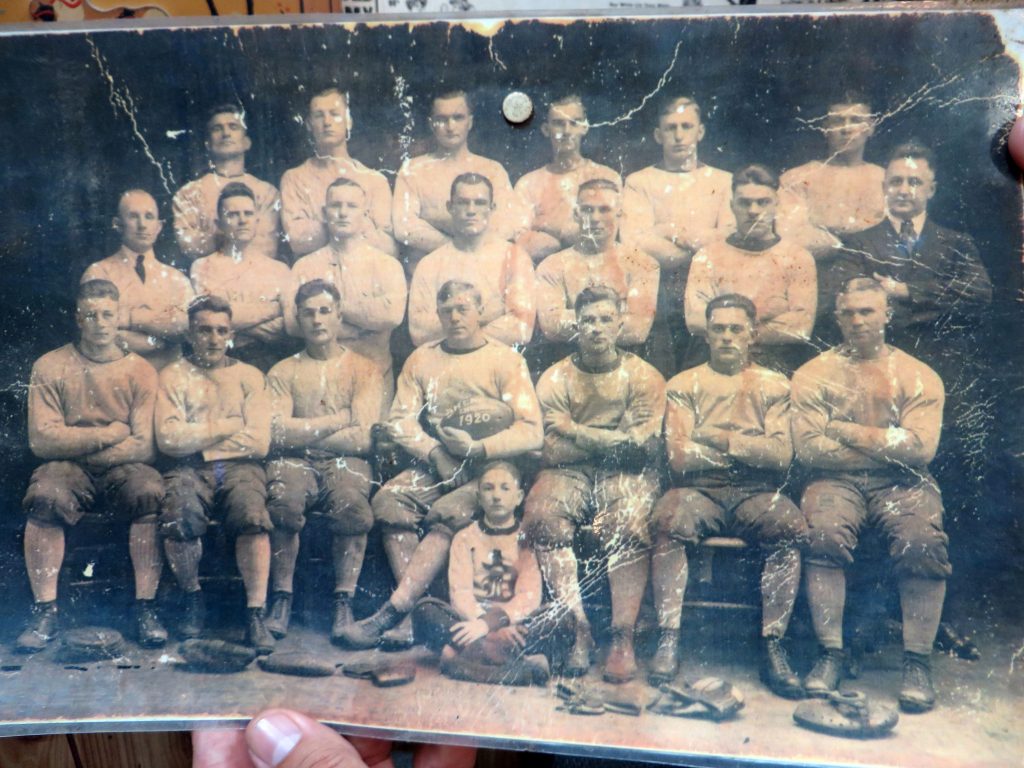

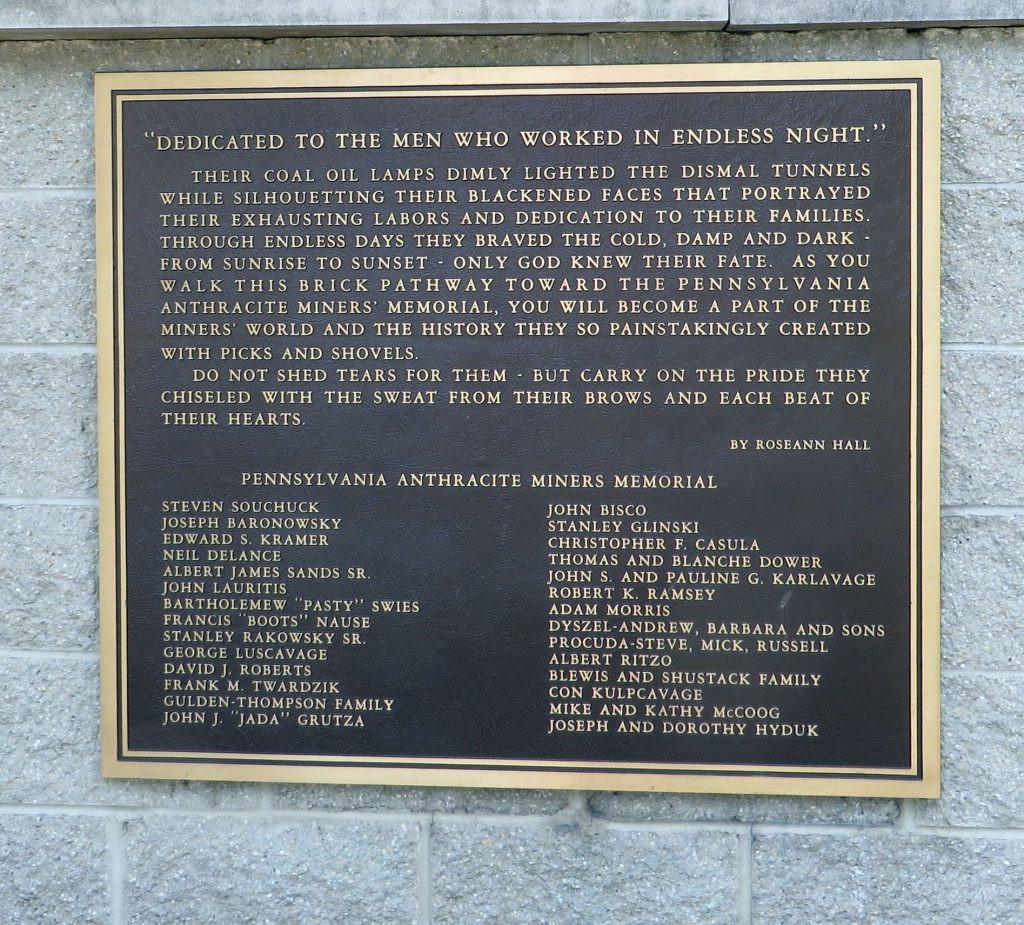

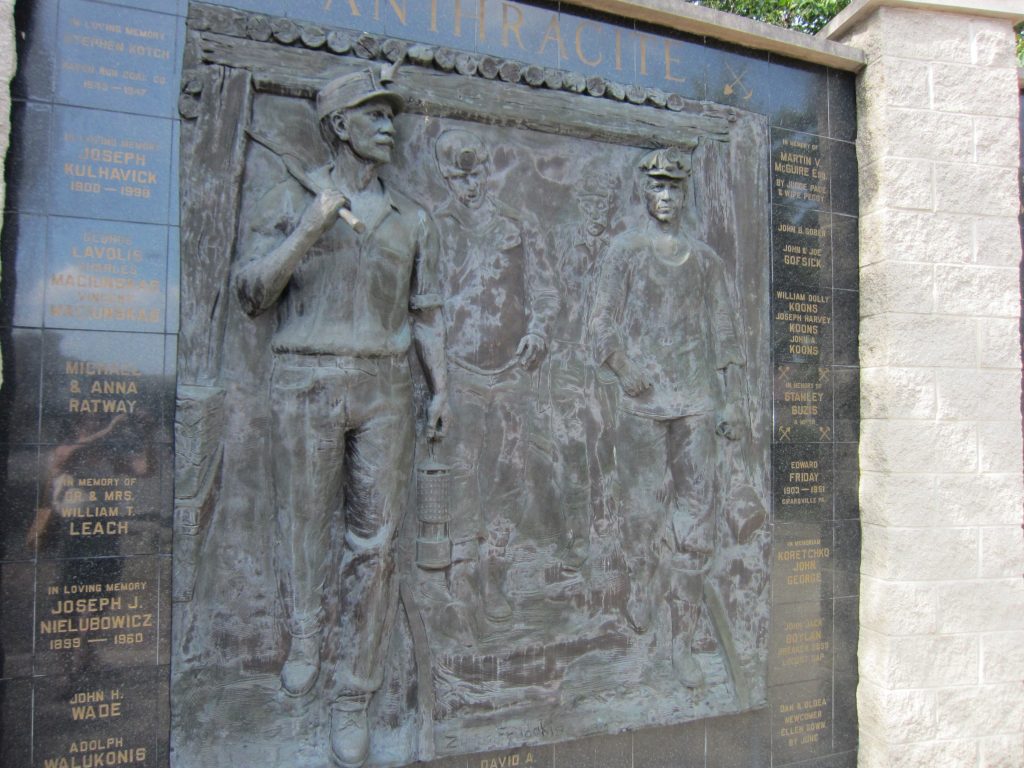

A fitting tribute was paid to the miners when Paul Swies of Shenandoah, now deceased, was chosen to represent the typical anthracite miner on a poster depicting labor's contribution to the winning of World War II. Dressed in his miner clothes, a small lamp attached to his cap, and holding a drill, he embodies the spirit of the knight of the black diamond.

This article is reprinted from Polish American Studies, Vol. VI. No. 1-2, January-June 1949, with permission from the Polish-American Historical Association.

- History of Pottsville and Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania – Republished from Pottsville Evening Republican and Morning Paper, (J. H. Zerby Newspapers, Inc.), III, 1176.[↩]

- Borough Records of Shenandoah for 1940.[↩]

- M. E. Doyle, “History of Shenandoah,” Anthracite Labor News, (September, 1905). [↩]

- Loc. cit.[↩]

- Chris Evans, History of the United States Mine Workers of America from 1860 to 1890. (Indianapolis, Indiana: n.d.), 1-34.[↩]

- McAlister Coleman, Men and Coal. (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1943), 64-74. [↩]

- F. P. Dewees, “The Molly Maguires: The Origin, Growth and Character of the Organization. (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott and Company, 1877), 23.[↩]

- Ibid., 24[↩]

- A. Monroe Aurand, Jr., The Molly Maguires. (Harrisburg: Aurand Press„ 1940), 6-7. [↩]

- Dewess, op. cit., 369.[↩]

- Pottsville Evening Chronicle, (November 13, 1883), 1.[↩]

- Historia Polskich Rzymsko Katolickich Parafij, Archidiecezji Filadelfijskiej. (Philadelphia, 1938), 33.[↩]

- MSS Reports in Bernardine Sisters Archives. (Reading, Pennsylvania), file for 1899.[↩]

- Parish Records – St. Stanislaus Parish Archives, 1898.[↩]

- History of Pottsville and Schuykill County, Pennsylvania 1171.[↩]

- Poles in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania - 11 December 2020