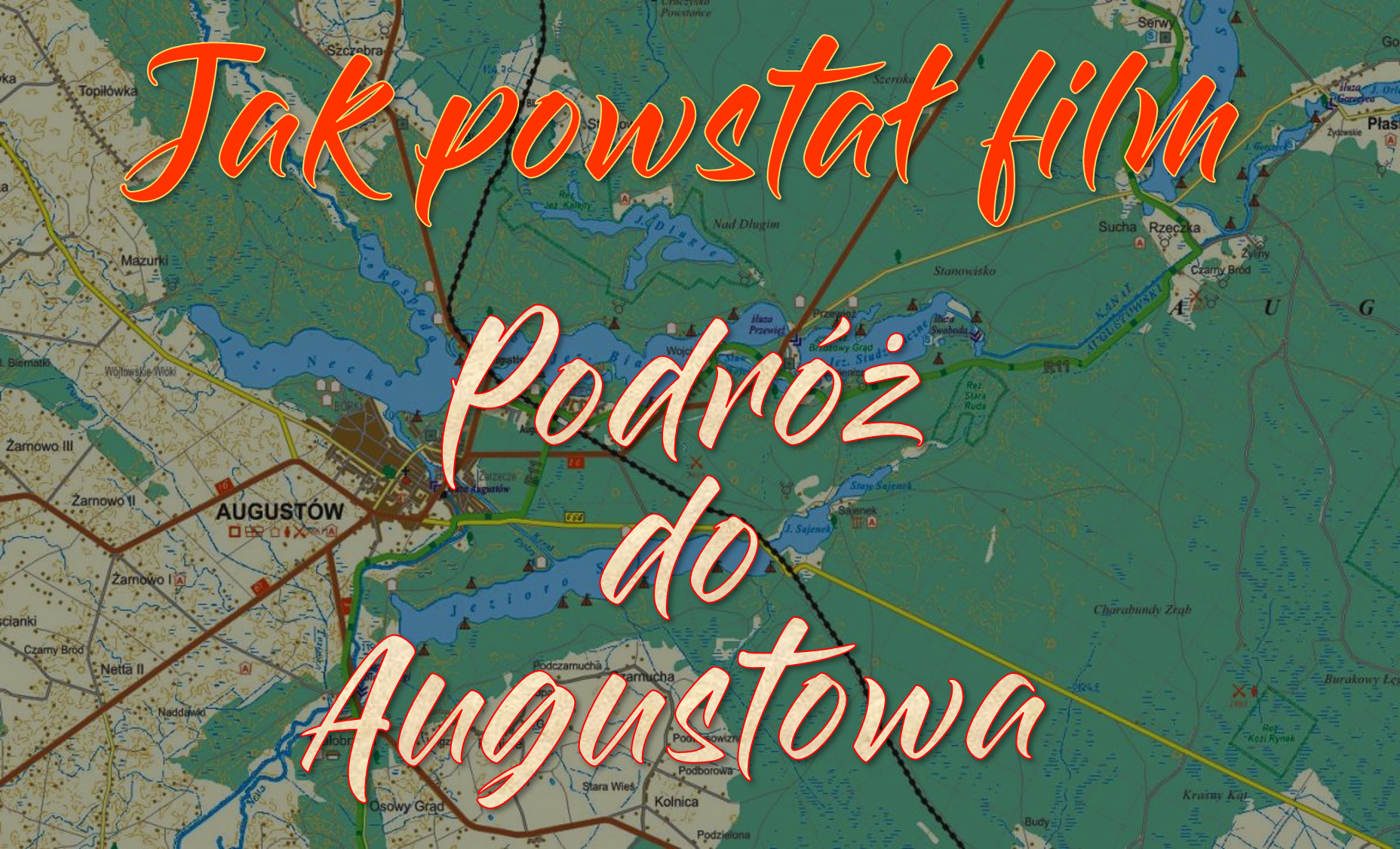

On our YouTube channel there is a movie by Naomi Sokol Zeavin entitled "Journey to Augustów". The materials for this film were shot in 1981 and it was Augustów from that time that was captured in the film. The film is about the history of Augustów Jews and their commemoration through the construction of a monument in the old Jewish cemetery, and the following, extremely interesting text, in turn, tells in detail how this film was made. If you are interested in the culture and history of the Jews of Suwałki, please support the translation of the "Memorial Book of the Augustów Jews": https://jzi.org.pl/en/product-category/kpza/

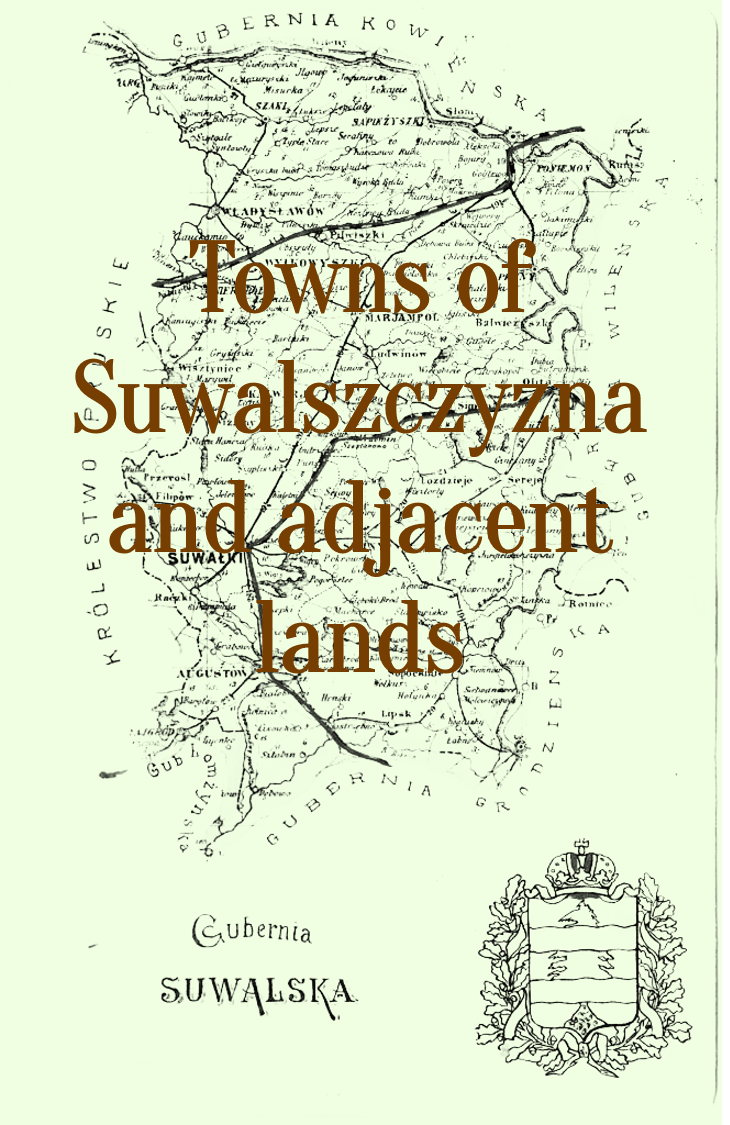

On an adventurous journey behind the then-Iron Curtain countries, I find myself with my former husband in Communist Warsaw, Poland. We were sitting in the lobby of our hotel, the year 1979. I asked Zasha, the tour leader if we could leave the group for a four-hour trip to the town of Augustów where my father was born. I wanted to see where many generations of the Sokolsky family had lived. The guide provided us with a jovial man who would drive us; he spoke Polish and German, but he couldn't speak English.

All the while during the drive up the narrow winding roads, my heart was pounding. At long last we reached the pretty town square in the beautiful lake region of Augustów. The first thing our driver did was go and ask the young blonde woman in the information kiosk if she knew where the Jewish cemetery was. Her name was Anna, she said she did not know but took us to her home nearby to pick up her mother Regina Buksińska, who was the only English teacher at their high school. Out of the house came this little woman, under five feet tall, in her late forties, with a huge smile as big as she was.

Regina immediately took us to the home of Józef Babkowski. He was a strongly built, husky man, seventy nine years old. The deep crevasses on his face told of a man that had lived hard and worked hard. Mr. Babkowski was thought of as the town historian. He had hidden a little Jewish girl all through the war, risking the safety of himself and his family. Mr. Babkowski remembered the Sokolsky family and said he had shopped in the two stores that they had owned. He put his hand up and held it out, not too high and said, "Oh, they were the good-looking little people." True to fact, my father was the tallest of the six sons and two girls and he was only five feet six inches tall.

He took us around the square and showed us where my family had lived. I said I wanted to go to the cemetery to pay my respects. Regina said "There is no cemetery," and Mr. Babkowski said "Oh, yes there is," and he led us on a long walk through the town to some dense woods. While I was pushing the branches away from my face, I realized the cemetery no longer existed. Mr. Babkowski continued to tell us in Polish and Regina kept interpreting, that the Germans had taken all the headstones and used them to build roads and sidewalks, they put the rest of the stones in the Jewish Ghetto. I asked "Are the bodies still here?" His answer was, "Yes." Standing on the graves of my relatives gave me an eerie feeling. In the woods was a lovely wooden house where once the bodies were prepared for burial for the Jewish funeral, a Polish family was now living in it. Right next to where the Jewish cemetery had been, the large Catholic cemetery stood. It was completely intact, not a stone out of place.

Mr. Babkowski then said, "Let's walk over to the other side of town where the ghetto was." We came upon a small area of small homes. In the comer of a large lot were many broken headstones, helter skelter with high grass growing around them. He then told us how in 1941, when the Germans walked into town, they took all the Jewish men from ages 15-65 and shot them in the woods near Szczebra, a total of one thousand and fifty men. He said the noise was so loud people in the town could hear the guns and it scared them.

We all piled into the car and drove to the woods, a short way out of town to see where this horrific event took place. The woods were made up of tall pines going up to the sky. My father had told me of the beautiful woods of Poland. At that point the trees didn't appear so lovely to me and I couldn't wait to start our trip back to Warsaw. I was feeling relieved that my grandparents had died a natural death in the early nineteen thirties.

I was really depressed on the ride back to our hotel. I became quiet, which is rare for me. I decided then and there I must do something so my relatives and all those who died in the holocaust must not be forgotten. It was hard to believe, not one person in the entire town of Augustów was Jewish.

After a few weeks of serious thinking, I called the Polish Embassy in Washington, D.C. and made an appointment with the first secretary, Mr. Bronisław Stawiński. I drove to see him, only forty five minutes from my home in Virginia. When he walked in the room, I thought immediately he looked like my late father. Sure enough, he told me his grandmother was Jewish and the family hid in the woods during the war. I proposed to him that I would like to restore the Jewish cemetery and build a monument to the Jewish people who perished during the holocaust.

Secretary Stawiński was very sympathetic and said he would get in touch with the mayor of the town1 to get permission to build a monument. The Mayor of the town said no to our first request, but we persisted and the second time, we got permission. Secretary Stawiński then got me in touch with the Jewish Organization for all the Jewish people in Poland; their headquarters were situated in Warsaw. The group was named Związek Religijny Wyznania Mojżeszowego, and Moses Finkelstein was president. Mr. Finkelstein did everything for us. He drew up the plans for the layout which I sent, and handled all the money exchanged. His partner in the organization was the non-Jewish bureau chief Jerzy Komack. Together they made a few trips from Warsaw to Augustów to meet with the Mayor and to work out where the monument would be and how large the fenced-in area could be.

Back home in Virginia, I decided to go into Christian cemeteries with large, tall headstones, to find a monument I liked. I found the one that was perfect in a cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia and took a picture of it. Then I went to a Polish stone cutter in Arlington, Virginia, who was kind enough to put the measurements down, and without a charge, drew a picture of the monument. He also wrote instructions of how to cut the stone and the kind of material to use. I sent the details and pictures to Poland and from that, they hired a sculptor, Tobiasz Jan Trzciński.

Two large projects were now ahead of me; one, to find other people from Augustów and two, to raise the money to build the memorial. Mr. Stawiński gave me the name and telephone number of the organization in New York, "Independent Suwalk and Vicinity Benevolent Association". It was organized in 1905. My father used to attend meetings there for years. One summer my parents took care of Stanley, the son of one of the lozmen, when he was going through a tough divorce. That's how close people were years ago.

One day I took the train to New York with my daughter Jill · to meet a member of the Independent Suwałki and Vicinity Benevolent Association who was from Augustów. He was a generous and elegant man, Sam Grodowski. He told me of two women who came from the area, Luba Lewinson and Rachael Nunburg. Rachael lived near me in Maryland.

I went to talk with Rachael the next week. When I came into the kosher grocery store she was sitting at her desk and refused to get up. She was rather stand-offish and leery of me. I could understand when she told me she had been in a concentration camp. After a while she warmed up and did promise to make a donation. I told her I would get in touch with her when I raised all the money.

I did a fund raising campaign by sending letters and calling people. I used my holiday list, my club memberships, the newspapers and radio. We received the largest amount of money from family and relatives. I was very active politically so I had a big base there. Donations came in from the Governor of Virginia, John Dalton, our Congressman, Joel Broyhill and Supervisor 2 Tom Davis.

There was an equal amount of gentile and Jewish people who donated. We did it and raised all the money we needed. Since I was a member of Screen Actors Guild and American Federation of Television and Radio, I thought why not film the ceremony. One of my former husband's generous patients, Mr. Don McNary became the backer of the film.

I took Polish lessons through a friend of Secretary Stawiński, a young women named Mira Creech3. She became my teacher and my friend. We really needed more money and her mother back in Warsaw helped us by exchanging money on the black market. Her sister Anna became my interpreter, and she also hired the Polish film team for me, Interpress. I was told to bring my own Kodak film because they were short of film in Poland.

In 1981, just one year after I wrote to the Jewish organization in Poland, we flew to Poland for the dedication of the monument. It was August, and the weather was really warm and no rain in sight. We stayed at the Hotel Victoria in the center of Warsaw, but spent most of our time at the Madelski's home of Mira and her mother. At this time there was little food, and yet they were so generous to us. Solidarity was on the rise and it looked like the Russians might come in by force and take over the city.

The situation was very tense and food was hard to get. You had to wait in long lines for bread, then go to another line for a little meat. It would take the day to get a sandwich. My friend Mira and her sister Anna even took some of the toilet paper from our hotel bathroom. They had police guarding the hotel so only patrons of the hotel could go in. People had money but nothing was in the stores. One day we stood in a long line to get a stuffed roll, not with a hot dog but with mushrooms.

This was a hard time to accomplish all we did, as Poland was under martial law4. The very next day while we were in Augustów filming and doing the dedication, back at our hotel in Warsaw, the Victoria hotel was surrounded by Polish soldiers holding off the solidarity protesters with guns. My film team was very worried about my safety and I was worried for their families.

We came to Poland with boxes of food containing sugar, flour, and cigarettes, gifts to all who helped us. As we were shooting a scene of me sitting on a bench in the town square a woman was screaming in Polish out the window, "Give us food. Don't take our pictures!"

The day before the ceremony we ran around and shot different scenes, for example the one in the woods with Mr. Babkowski and the interviews in the hotel. The next day at the ceremony I was so excited they had Polish flags outlining the forest right up to the monument at the cemetery. There were plants all around the fenced-in area, donated by the city. Twenty eight guilds presented flowers and put them on the monument. The boy and girl scouts stood honor guard and also presented flowers. The Communist Secretary spoke first about "this historic occasion." Next the mayor spoke and welcomed all of us and mentioned the citizens of Poland who died and were buried in this holy ground. Father Zdatowski the local priest spoke and said he had great respect for Jewish men when he too was in the concentration camp in Moghaven5. He admired their will to live, no matter how hard they struggled; they were whipped pulling wagons and they would keep getting up. He spoke of remembering the Jews and respecting their memories.

Mr. Finkelstein spoke saying, "One third of the town's 4,000 people were Jewish, living in Augustów at the time the Germans moved in. They led productive lives side by side with gentiles of the community. They were merchants, skilled tradesmen and professionals. Some of them owning mills and numerous stores. It was a thriving Jewish community. They had a library and helped the poor. They had many synagogues to pray in as you have your churches. They also trained many non-Jews and taught them many trades. They were truly neighbors and friends." Rabbi Hertz, the visiting Rabbi chanted the beautiful words for the dead, "Al moleh rak hamim."At this time there were no permanent Rabbis in Poland. Rabbi Hertz came from Brooklyn, USA.

I spoke for a few minutes and the speech I studied for half a year to say in Polish went right out of my mind, when I saw all those faces looking at me. I put a stone on the monument and said in the Jewish tradition we leave stones on the grave we visited to show we were there and we cared. Anna translated all I said, I ended with the words "jen-koo-yea" in Polish (thank you) and that made them all smile and clap. I then dug a small hole in the Polish soil and buried the tin can with all the names of those who donated money to make this dream come true.

The three people who I contacted in America came to the dedication. Mr. Sam Grodowski left Augustów in the 1930's as a young boy. Rachael Nunburg, the survivor of the ghetto in town, who had spent three years in Auschwitz and whose father was one the men shot in the woods. Also Luba Feldman attended, a sweet women from New Jersey. Right after the ceremony, Mr. Grodowski made arrangements and paid for the headstones that were in the Jewish ghetto to be moved and put behind the memorial.

All four of us had given donations, because of that fact we put the four family names on one side of the monument: Sokolsky, Grodowski, Lewinson and Slowatychi. Followed by these words, "Consecrated Land ...In This Cemetery Are Buried Thousands of Jews from the town and community of Augustów."

One woman came up to me right after the ceremony and said in Polish how happy she was that there was now a memorial. She had a Jewish neighbor who was her good friend and they were very close.

After the ceremony we were all joyful but that soon changed to tears for me. The cameraman came to me, all upset and said someone stole the blue plastic bag that he left on the ground with the film we shot the day before. Seems they thought it was food. The police tried to find it and many of the town's people looked in the trash bins and it was even announced on the loudspeakers driving through the town. To no avail, hopeless.

We only had the day's ceremony filmed. I said that's it, forget it. I just could not think of what to do. But Anna and the crew were wonderful and insisted we take the shots over the next day before we went home. The cameraman got up at dawn to surprise me and rolled up his pants and went wading in the Netta River with his camera to get a fabulous shot of the wide river, which my father was a town hero for swimming across. The film "Journey to Augustów'' is today on CD's and in both the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. and in Yod Visham in Israel.6

I have heard from numerous people that have viewed the film in Washington in the Holocaust Museum research room. A few of them have gone back to Poland to visit the cemetery and monument. One family, the Fishbines had a bus full of family members tour Augustów. They added a large stone of their own at the cemetery. Another man, Hank Hchonzeit, went to Augustów with his daughter. Lovely Regina was both families' guide.

Regina my angel has been watching over the cemetery for the over thirty years. The officials in town are in charge of the cemetery's upkeep but when things are broken, I have to take care of the repair. Regina and her family go and make sure the area is clean and take the leaves off. They also bring flowers and candles. The town is one hundred percent Christian and yet she always finds flowers there or candles, resting on the base of the monument. In the last few years, there has been graffiti and damage. Without one Jew in town, it is beyond me that swastikas and destruction have taken place each year. The mayor of the town does punish those who do the damage, but many get away with it.

I have been back three times since the ceremony, now over thirty years ago. I have made many friends at the Polish Embassy here in Washington.

Doors have been opened to me and some exciting experiences have made my life fuller and more memorable, due to my calling to restore the cemetery. The first event would be when the doorbell rang and two young handsome men, dressed in dark suits were at my door. They showed me their cards, from the FBI and wanted to talk to me. I invited them in and thought what have I done? Seems they have been taping me and watched and listened to all my phone calls and seen my comings and goings to the Polish Embassy over the years. We also entertained at our home many of the dignitaries from the Embassy.

This was the time of Communism in the 1980's and the Ambassador to America from Poland had just defected, Ambassador F. Romuald Spasowski in December 1981. They asked me if I could get Secretary Stawiński to defect. I did speak to Bronisław about it but he had family back in Poland so he said he would have liked to but couldn't; he would fear for their safety. A few years later the FBI came again and asked me to spy on the new first secretary who I had become social friends with, Krzysztof Nowakowski. I did my best, but got no interesting new information for them. Chris is still my good friend to this day. A few years later when I visited Poland, he and his wife and son took care of me when I went to revisit Augustów.

Just a short time after my visits from the FBI I was getting a presidential appointment from President Ronald Reagan and I wrote down the two visits and names and dates on my clearance. Happy to say, it didn't matter and I got my appointment in 1985.7

Another exciting event that took place through the Polish Embassy in 1991, I became friends with the now noncommunist Embassy of Poland, the new first secretary Andrzej Jarecki. He was a very tall, lean and debonair famous playwright and movie director in Poland. He had received many awards, one equivalent to our Oscar8. Due to a rise in Anti-Semitism around the world I wanted to produce a new version of the film and have it in Polish and English. Secretary Jarecki helped me do just that by doing some of the voice over in Polish, and helping with the translation.

So much of the anti-Semitic incidents were happening in France. This lead me to get in touch with the French Embassy in Washington. I began working with the press secretary Pierre Gunard, who opened all doors to me. I went through all their papers and files and added pictures from France in the new version of "Journey to Augustów."

The new version was a success and I got an invitation to show the film at the Jewish Festival in San Francisco. Secretary Andrzej Jarecki's close friend was the 1980 Nobel Prize poet Czesław Miłosz who was then teaching at the University of California in Berkeley. He wanted him to see the film. With his letter of introduction, and a call from him to Mr. Miłosz, I was invited to his home. He amazed me to take so much time from his busy dedicated committees at lofty institutions. How were you, this small, young woman single-handedly, and in so short a time, have a monument to Jews erected behind the Iron Curtain?"

My answer was a thousand hands were helping. Many hearts go to fulfill a dream. A Jewish belief is that when you are thought of you live again, and with the memorial, people must think of the Jewish people who once lived there. They live again.

I truly believe it was God who guided me all the way on this journey, for without him, I could not have succeeded. I am just one of his instruments.

- In those days at the top of city authorities was not mayor but the head of the city council[↩]

- Fairfax County Board of Supervisors[↩]

- https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mira_Modelska-Creech [note ed.][↩]

- The author is wrong here, because martial law was introduced only on December 13, 1981 [note ed.][↩]

- It is probably the Mauthausen concentration camp[↩]

- We also donated a copy with the Polish soundtrack to the Augustów Cultural Institutes [note ed.][↩]

- The author was nominated as a Member of the Art Advisory Committee on May 14, 1985 by President Ronald Reagan. [note ed.][↩]

- Here the author probably exaggerated a bit. The film "Marysia and Napoleon" based on the drama by Andrzej Jarecki received a distinction in 1967 at the International Festival of Color Film in Barcelona[↩]