My interest in this subject area began after I discovered that two ancestors of mine, Stanisław Szociński, living in Rogowo, and Jan Słomka of Dziekanowice, both in the Poznań province, were listed as tabernator, Latin for innkeeper. I thought this was pretty fascinating as I am, let’s say, pretty familiar with the tavern life – the sights and sounds, the comradery and social aspects, and of course, the drinks. It has been part of my life for a long time. To know that I had some ancestors in the business seemed like life coming full-circle.

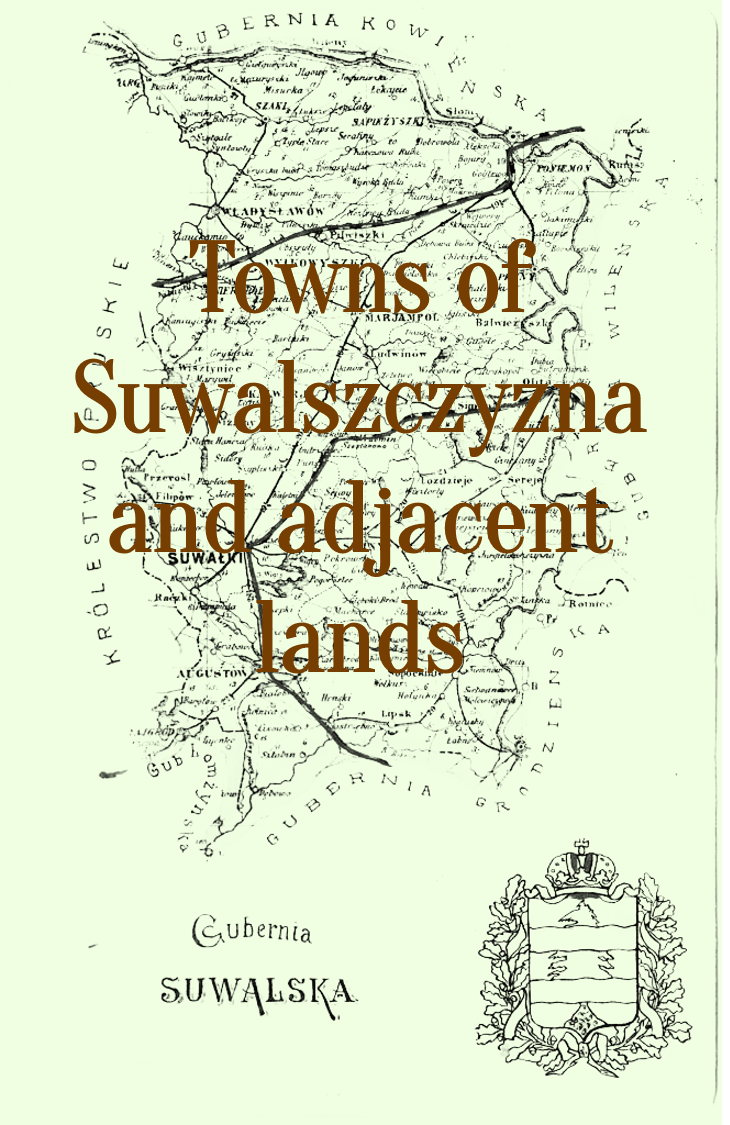

Early in the 1990s, I was researching a branch of my Orbik family in Barglów-Kościelny parish who held the occupation strzelec lasów, or forest shooter, which led to a nice article about forestry occupations 1. While researching that article, I noticed a fair amount of non-farming occupations in this otherwise farming community 2. I examined baptism records between 1855-1867, primarily to see what other occupations existed and whether some of the farming occupations, like gospodarz, pokątnik or luźniak, changed titles after the emancipation of Polish peasantry in 1862. I went through every baptism record from that time period because the Geneteka database, at that time, only occasionally mentioned an occupation, and then, only of the father. This was a very time-consuming process.

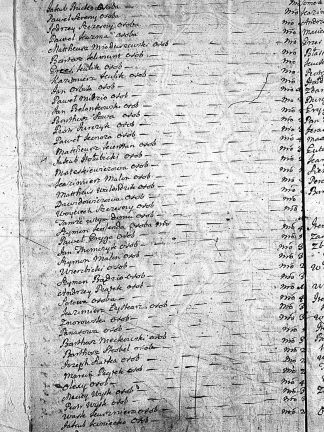

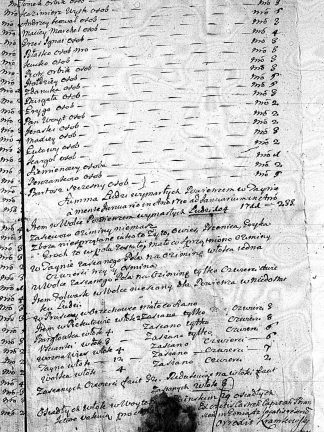

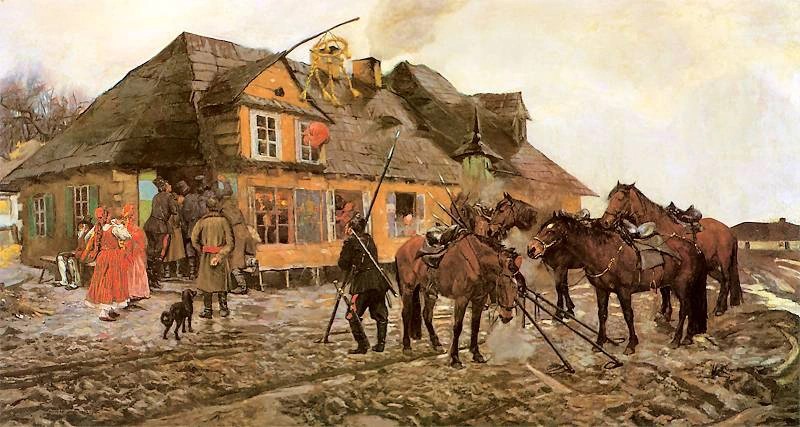

Among many different non-farming occupations, I was fascinated to learn about the network of alcohol production and distribution on the various estates and villages. There were distillers, gorzelny/gorzelnik, beer brewers, piwowar, innkeepers, karczmarz, and taverners/bar tenders, szynkarz, wine distributers, winnik, and liquor merchants/distributers, propinators. There were also a host of supporting occupations such as millers, młynarz, barrel makers, bednarz, and coppersmiths, kotlarz. The alcohol production occupations were located near the largest estate manors, while inns and taverns were spread out among the villages.

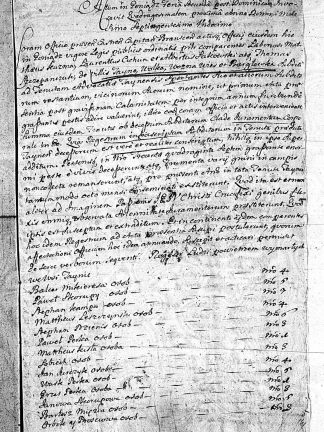

One of the things that puzzled me was that everyone involved in alcohol production during those years were Christians. Over the years, as part of my curiosity about my ancestral homeland, I had read many non-fiction historical books about Poland, but also, as many literary works I could find in English. In these novels, the innkeepers were always Jewish. But why was this different in my ancestral parish? In 2012, I contacted the managing indexer for the Barglów-Kościelny parish records for Geneteka, Bartosz Choroszewski, and asked him if he would share a spreadsheet of all the people involved with alcohol production and distribution, which he graciously did. What the data showed was that from 1807 to 1812, Jews were listed as the leaseholders of the inns and taverns. After that, the term leaseholder disappeared, as in arendarz karczmy, and the words karczmarz and szynkarzappeared. I had read that sometime around this time, that Jews were banned by the government from running such establishments, mostly because of the anti-Semitic polemics that Jewish taverners and innkeepers were ruining the polish peasanty by luring them to alcohol abuse and then ruining them financially through trickery and deceit 4. Satisfied with that explanation, I let the matter go for some time, hoping someday to delve back into the topic.

In the meantime, I read a couple of books about the portrayal of Jews in Polish literature, Stranger in Our Midst: Images of the Jew in Polish Literature, by Harold B. Segel 5 and The Jewish Tavern Keeper and His Tavern in Nineteenth-century Polish Literature, by Magdalena Opalski 6. They seemed to confirm the above-mentioned sentiments, with the exception of Jankiel, the tavern-keeper in Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz, who was described as a good, honest, and patriotic Jew 7. W zeszłym roku nabyłem książkę Yankel’s Tavern: Jewish Liquor & Life in the Kingdom of Poland , by Glenn Dynner. This was a game-changer for me and helped me understand what was happening in much greater depth. Rather than only relying on Non-Jewish, Polish literature, Dynner researched individual petitions for liquor concessions in the treasury documents from the Polish archives, as well as requests for advice on liquor-related matters from Rabbinic archives 8. Together, they paint a much different picture of what was really happening in the alcohol production and distribution then literature or official Russian government statistics and legislation could show.

Continue reading Produkcja i dystrybucja alkoholu w powiecie augustowskim w XIX wieku

- Orbik, Jay M. Forest Guards in Podlasia and Mazuria, East European Genealogist, Journal of the Eastern European Genealogical Society, Inc., Winter, 2010, 6-23.[↩]

- Orbik, Jay M. Non-Farming Occupations in a Farming Community, Pathways and Passages, Journal of the Polish Genealogy Society of Connecticut and the Northeast, Summer 2010-Winter 2011, 26-32.[↩]

- Chełmoński, Józef. „Przed karczmą – Pejzaż jesienny”, 1882, olej na płótnie, 70,8 x 130,6 cm, Muzeum Okręgowe, Bydgoszcz[↩]

- Słomka, Jan and William F. Hoffman From Serfdom to Self-government: Memoirs of a Peasant from Serfdom to the Present Day. Chicago: Polish Genealogical Society of America., 2019, 124-125, 275, 382.[↩]

- Segel, Harold B. Stranger in Our Midst: Images of the Jew in Polish Literature. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996. [↩]

- Opalski, Magdalena. The Jewish Tavern Keeper and His Tavern in Nineteenth-century Polish Literature. Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center; The Center for Research on the History and Culture of Polish Jews, 1986.[↩]

- Mickiewicz, Adam, and Kenneth R. Mackenzie. Pan Tadeusz. 1st American ed. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1992, 164-166.[↩]

- Dynner, Glenn. Yankel’s Tavern: Jews, Liquor, and Life in the Kingdom of Poland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014, 9-13.[↩]